Position: 43°13’12.1″N 9°00’02.4″W

Crossing the Bay of Biscay from La Rochelle commits you to being at sea for at least 350 nautical miles. Distance is only part of the equation. What those miles are really telling you is how many nights you’ll be awake for. In good conditions Aleta will cover more than 150 nautical miles a day. We know that because that’s what she averaged crossing the Atlantic on a beam reach in a steady 18 knots of wind for 15 days.

Summer, broadly speaking, is a little less lively and winds a little less reliable than other times of the year. I figured we’d be out for three nights and based on the forecast we’d hoist the iron genny (start the engine) for the last leg of the trip. Currents would either be with us or against us depending on where we were and the time of day.

Once committed to heading offshore your life depends on how seaworthy your boat is. And your ability not to hit an orca or another ship in the middle of the night. On shorter trips of a few days getting enough rest can be difficult. Difficult because the discipline of standing watches gets elided. After all, it’s only a few days, right?

On Aleta we stand three-hour watches. Perhaps the best description of what you’re supposed to do when you’re not on watch is rest. Rest, sleep, relax, unwind. As crew, your only responsibility is to charge your batteries for your next watch. With only two of us on board, three hours of downtime is rarely enough to fully rejuvenate. Making watches longer does not, in our experience, measurably improve things. Sleep deficit increases steadily, so we work on resting as much as we can when not on watch. That and keeping well out of the shipping lanes – just in case.

Visitors

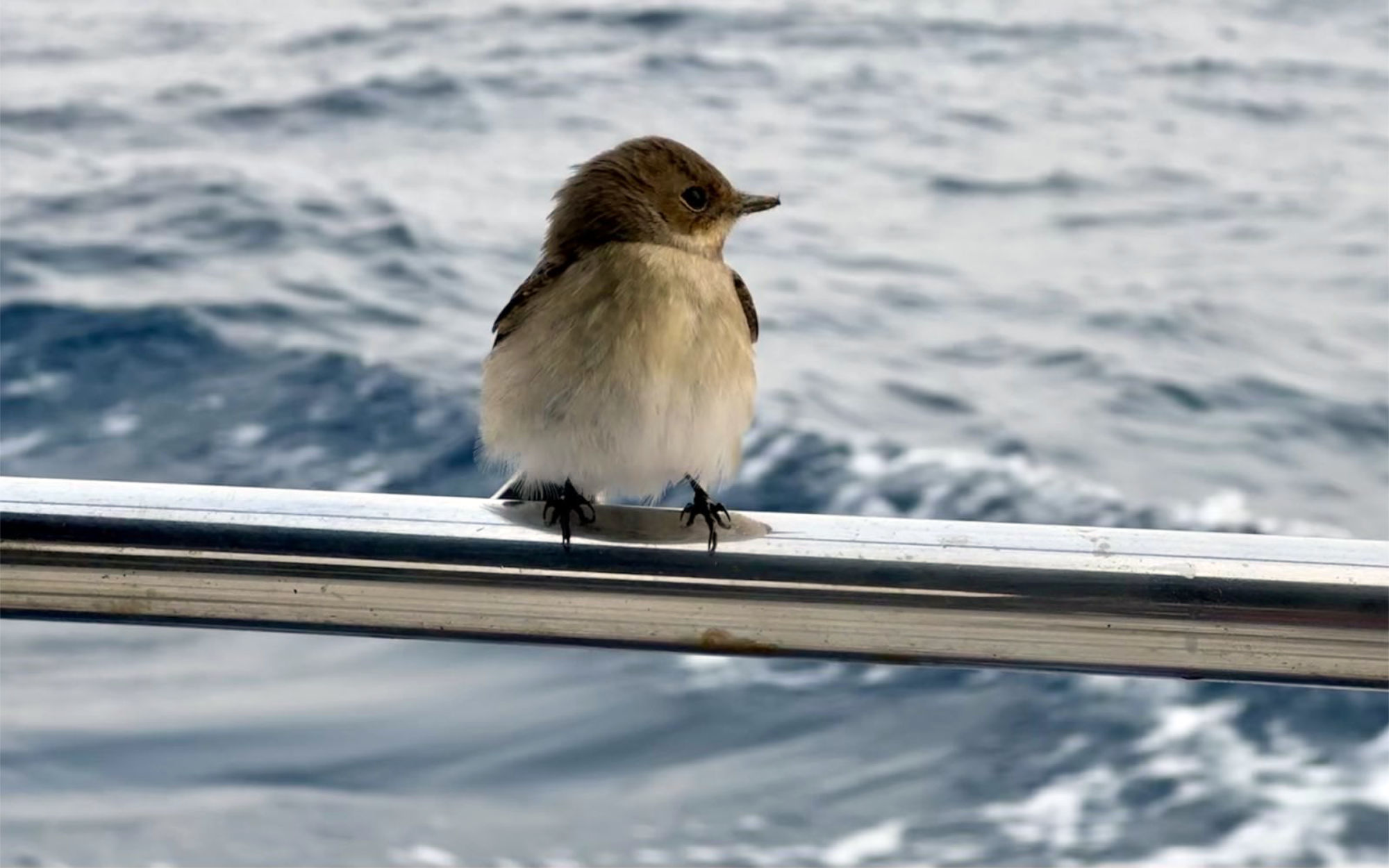

The further offshore we go, the more excited we get about visitors. Dolphins, whales, flying and jelly fish keep us rooted in our environment. Pelagic seabirds like shearwaters and petrels are always welcome. But what pulls our heartstrings most are the small birds that seemingly defy physical limits. Swallows, one of the great migratory birds, occasionally stop by. A day out of La Rochelle an exhausted spotted flycatcher landed on Aleta’s davits.

Ruffling her feathers against the chilly air she eyed us warily and then took a quick look around. She quickly realized the stern enclosure was where our family of spiders hangs out. That might mean a morsel or two of better food than the bread and water set out on the side deck for her. Spotted flycatchers summer in northern Europe and winter in North Africa and, according to the RSPB, are moderately difficult to spot in the UK. We consider ourselves fortunate she stopped by.

One of the advantages of Starlink’s mobile internet service is you’re mere milliseconds away from identifying a bird you’ve never seen before – even 150 miles offshore. The downside is you’re never disconnected. It is also expensive. Twelve miles or more away from the coast Starlink’s maritime pricing kicks in. For less than three bucks a gigabyte you can eat all you want. The only trouble is a gigabyte ain’t what it used to be. Anything ‘high definition’ (720p or more) on YouTube will suck down one to three gigs an hour. That adds up quickly if you’re not paying attention. Fortunately, useful information like weather forecasts requires far less data.

La Costa da Morte

Treacherous and rocky, the sundered, crenelated shore of Galicia’s Coast of Death earned its name from centuries of shipwrecks. Running from Finisterre to Malpica, the shoreline offers some of the worst weather in Europe. Throw in brisk tidal currents and predatory orcas and you have the recreational sailor’s equivalent of wandering onto the wrong side of the tracks. Unless you go in settled weather that is, when the area’s coves and beaches are nothing short of wonderous.

After two nights and three days at sea we decided to anchor for a night and recuperate before turning the corner. Laxe’s long white beach, protective sea wall, and sandy bottom seemed just about perfect. From the water, the city looks a little brutalist. Blocky towers of white and pastels provide accommodations for a surprising number of tourists. Spanish holiday makers, if you don’t know, like nothing better than eating dinner at 11:00PM and dancing until sunrise. Our quiet anchorage turned cacophonous. Disco beats resonated outwards, across the water, vibrating Aleta’s rigging. By the time the pounding stopped at 6:00AM local fishermen were put-puttering out of harbour towards the rich fishing grounds just around the corner. The sound of their outboards a comparatively mute staccato.

Daily Dolphins

Blearily we made coffee and reviewed the latest orca sightings. Shoals of fish off the Death Coast makes it popular with orcas. When they’re done eating, they can play bumper cars with a boat or two and call it a day. Several websites track orca sightings and physical contacts. From what we could tell, most of their activity remained further east near San Sebastian, or further south towards Porto.

Motoring through the morning’s flat calm the clear water was almost free of other boats. Five miles north of Cape Finisterre we found our daily dolphins. First a fin swam alongside. Then a couple broke the surface, arcing up and out with a spray from their blowholes. In a few seconds, another four joined and we had a small pod running alongside. Dark grey on top and ecru underneath, these were our now familiar Atlantic dolphins. Moving forward they swam to Aleta’s bow. We quickly followed them and walked out along the bowsprit, smiling as they turned sideways to look at us. A mother and her calf joined for a spell. The calf sticking close but clearly enjoying their time with Mamma and her extended family.

The dominant northerlies filled in a couple of hours later, and by 2:00PM blew 20 knots on the stern just as we passed Finisterre. On jib alone, we romped along at seven knots in four-to-six-foot seas making great time. Vigo was still too far for that night and we opted for a sheltered cove about three hours out. Rounding up in 25 knots of wind meant a quick anchor drop with fingers crossed for a quick set. She hooked up immediately and we relaxed as the wind steadily dropped taking the thrum of the rigging with it. Sleep deprived we fell unconscious until the sun gently broke through the pine trees above the beach.

Vigo

The marina at the Real Club Náutico de Vigo is our preferred spot when we’re in that town. Unfortunately, our friends Bob and Eva had returned to the United States a little earlier than expected and we’d missed them. Instead, we added my daughter Emma and her husband Jarno as temporary crew for our trip down the coast of Portugal. Dedicated followers of this blog will recall their Adventure Wedding in Chamonix last year and Jarno’s trip with us through Sweden’s west coast. Jarno has since become keen on sailing and both kids got their cruising certificates last year. They arrived dockside early after an overnight flight from their home in Malta.

The day’s forecast looked promising. During breakfast we considered making a couple of day sails to shake the crew down. Then, depending how they felt we could consider an overnight. Something neither of them had experienced. Since all of us had spent enough time in Vigo in the past five years, we dashed through a grocery store for a few provisions and headed back to the marina. At the turn of the tide, we slipped our mooring and headed south through Vigo’s busy shipping lane. A steady 12 knot breeze picked up and we heeled nicely, touching six knots. It was shaping up to be a good day’s sailing.

A great post thank you so much. It provided a wonderful little respite from the day.

Thanks Mark! I trust you’re all doing well!